|

Interview with Milan Dragicevich on The State of Shakespeare podcast. Words, words, words. Milan Dragicevich is fascinated by what he calls “the verbal surface” – a place where rhetoric resides and where you will take your voice to the borders of your personality. Milan believes that rhetoric is not just the art of persuasion but a chance to contribute to something bigger than ourselves. http://stateofshakespeare.com/?p=6950

Milan discusses language-driven performance, lost secrets, passion for speaking, and even unleashes a monologue from Richard III. (October 2020) |

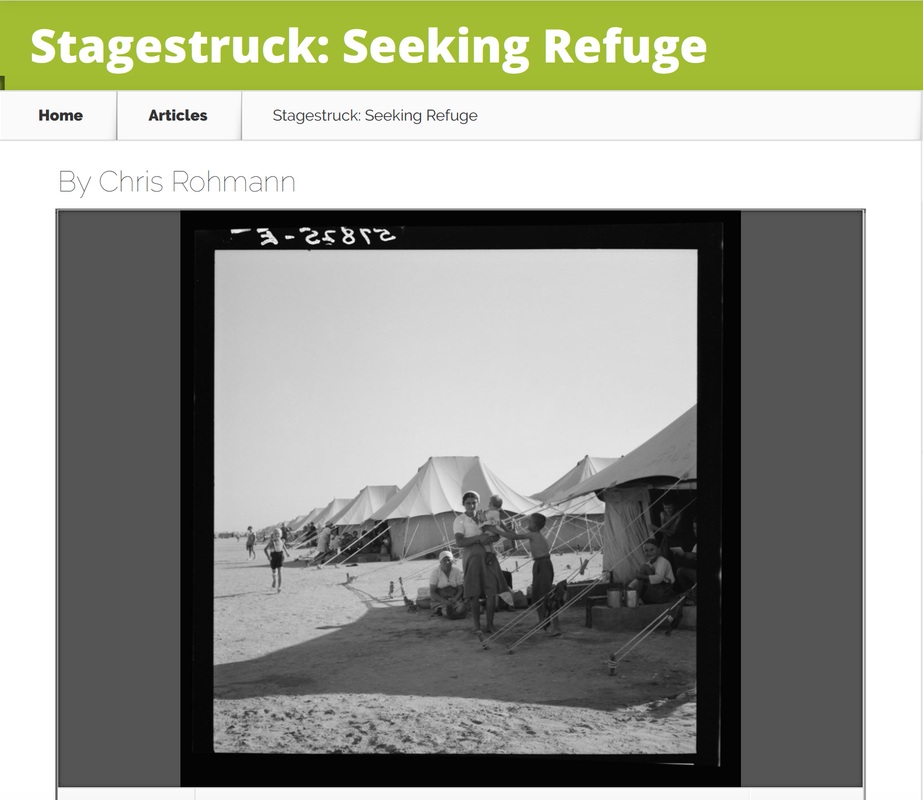

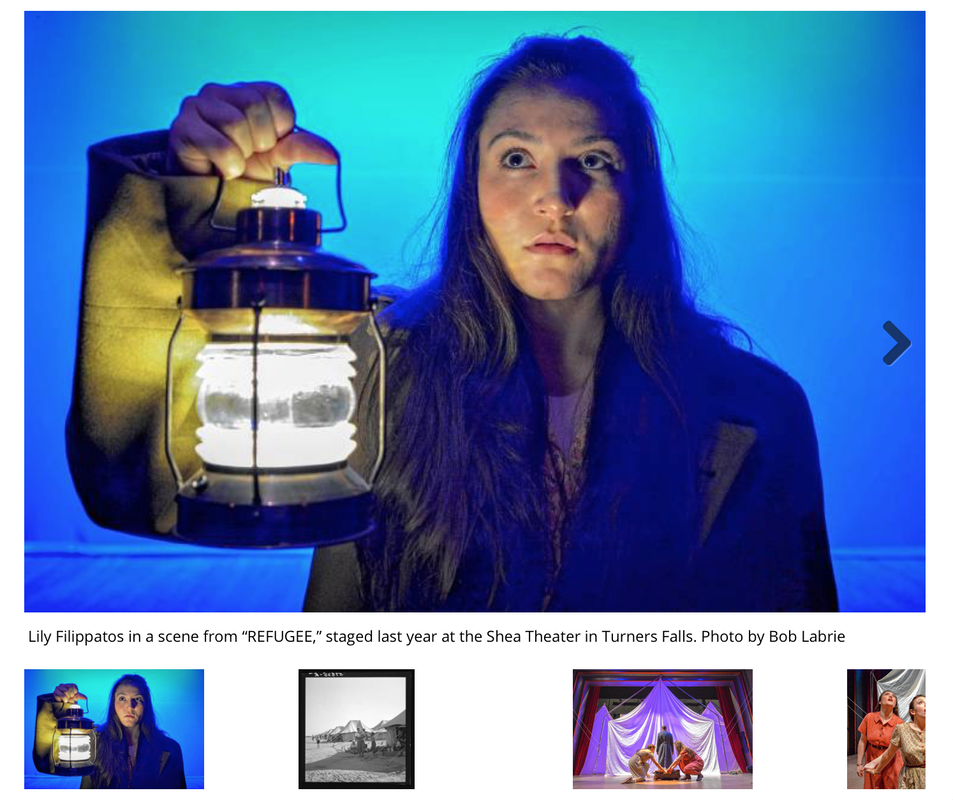

Theater Review of Milan Dragicevich's "REFUGEE", from Valley Advocate.com, February 2017, by Chris Rohmann

New England Public Radio interview with Milan Dragicevich, REFUGEE premiere, December 2016

WRSI "The River" Radio Interview: REFUGEE Goes to Serbian International Theater Festival, September 2018

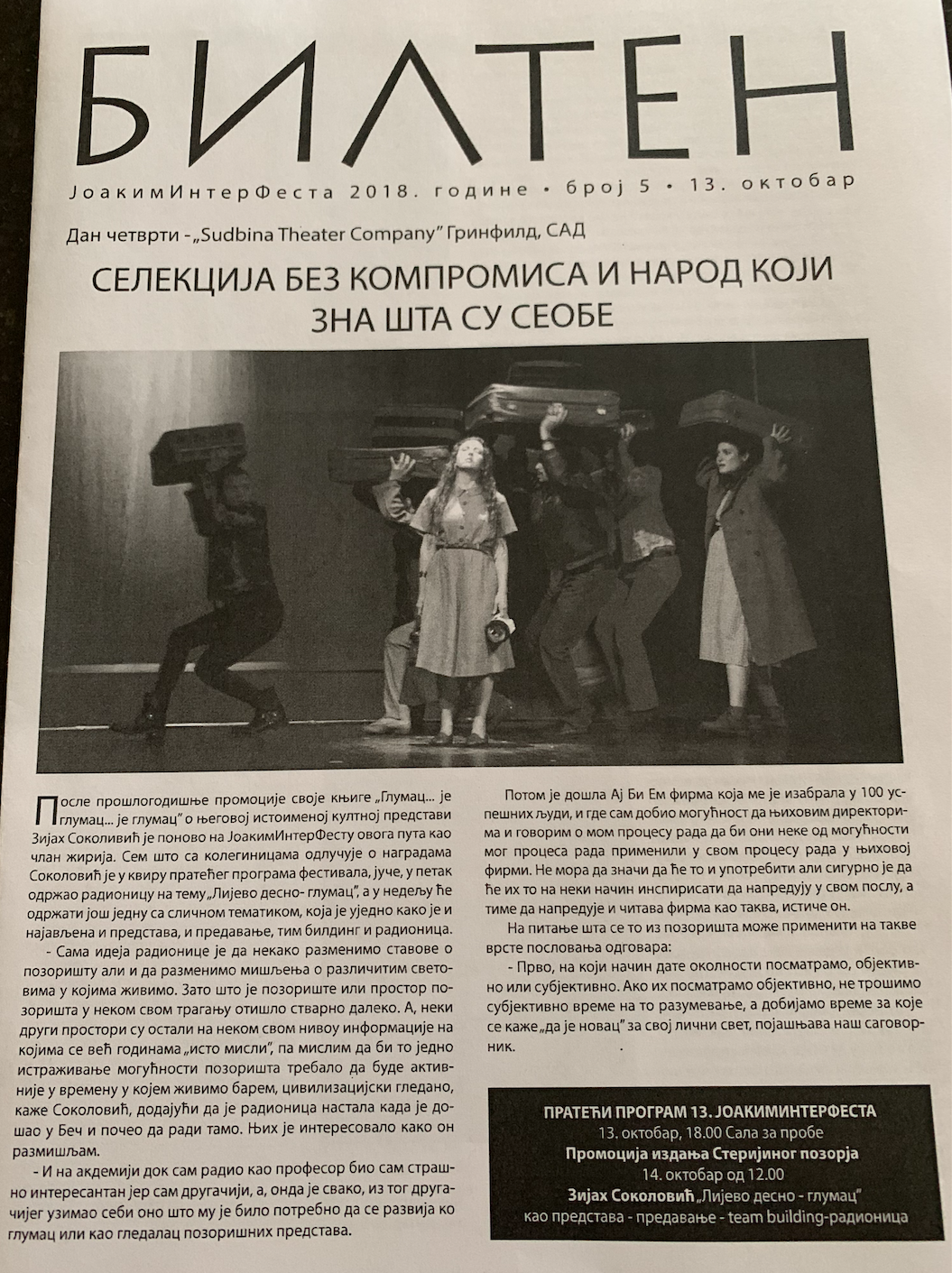

Joakim Interfest Serbian International Theater Festival's BULLETIN, covering the Sudbina Theater Company's production of Milan Dragicevich's "REFUGEE." Front cover production photo is from "REFUGEE" at the festival (Oct. 2018).

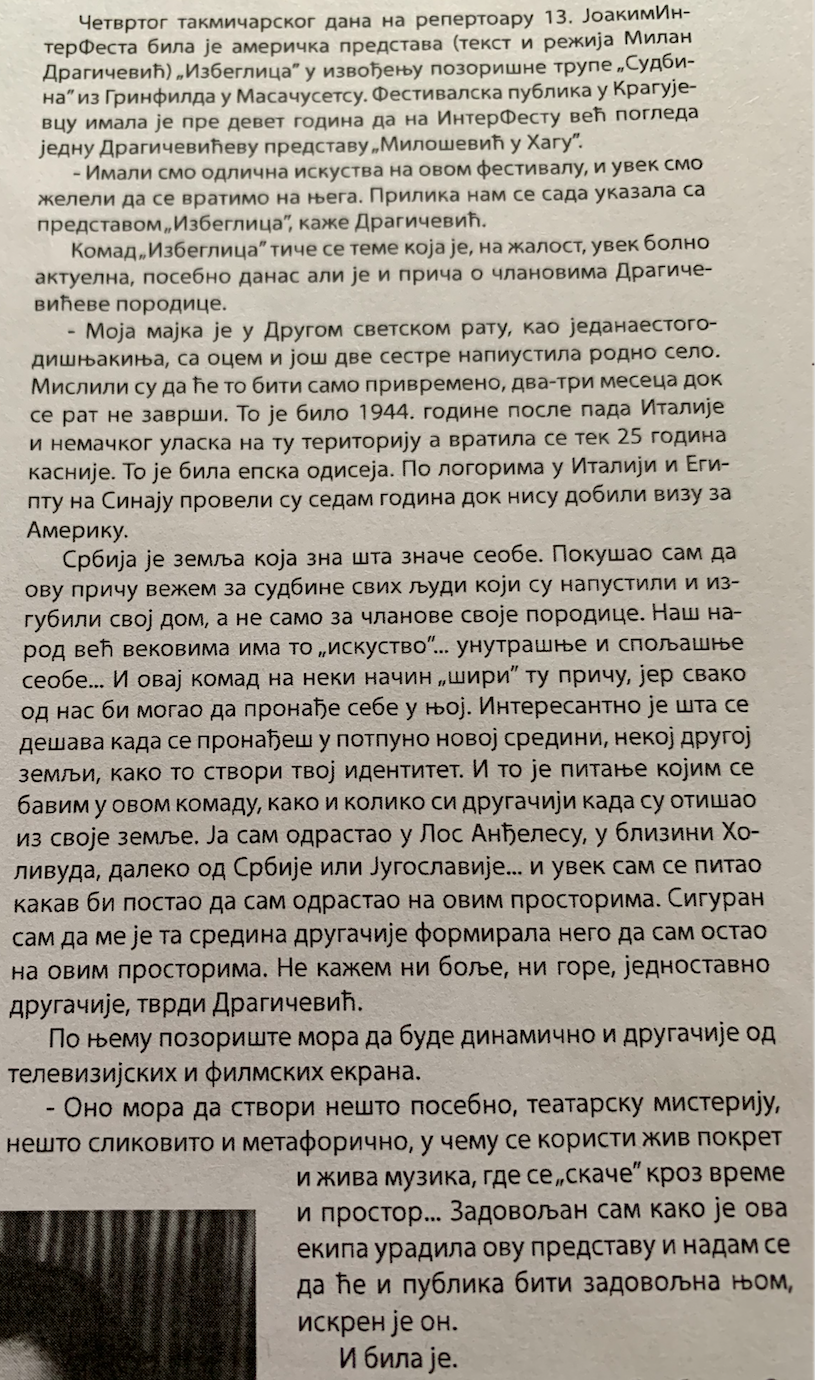

Background and interview with Milan Dragicevich, Joakim Interfest, Oct. 2018

TRANSLATION OF INTERVIEW WITH MILAN DRAGICEVICH AT JOAKIM INTERFEST IN SERBIA, OCTOBER 2018

On the fourth day of the festival, in repertory at Joakim Interfest, was the American production (written and directed by Milan Dragicevich), Refugee, presented by the Sudbina Theater Company, based in Massachusetts. Nine years ago, the Festival’s audience in Kragujevac watched Dragicevich’s earlier play, Milosevic at The Hague.

“We had a wonderful experience at this festival [nine years ago] and we had always planned to return. The opportunity finally presented itself with our new play, Refugee,” noted Dragicevich.

The play Refugee deals with a theme that unfortunately is always painfully actual and relevant, particularly today, with this specific story focusing on the Dragicevich family.

“During World War II, my mother, as an 11-year-old girl, left her village home with her father and two sisters, thinking that it would be a short temporary displacement of 2-3 months. That was in 1944, after the capitulation of Italy, followed by the German invasion of Yugoslavia. Twenty five years would pass before she returned to visit her homeland. It was an odyssey. Living in refugee camps, in Egypt on the Sinai and later in Italy, she and her family spent 7 years as displaced persons, until they received permission to relocate to America.”

Dragicevich continued: “Serbia is a country that knows the meaning of exodus and migration. My goal was to tie this story with the destiny of all peoples who are forced to leave their homes, and not only focus on my particular family history. The Serbian people, for centuries, have this “experience” – both interior displacement and exterior migration. So this play, in its own way, “widens” this story, because each of us can find oneself in its narrative. It is interesting to observe what happens to an individual when one suddenly finds oneself in a completely different or foreign environment, in another land, and one must create a new identity. And that is the question with which I grapple in this new play: How—and in what ways—do we change when we leave our homeland? I was raised in Los Angeles, near Hollywood, far from Serbia or Yugoslavia, and I always wondered how I might have developed differently had I grown up here, in the Balkans. I’m certain that my American environment shaped and influenced me in ways quite different than if I had lived here [Serbia]. I’m not saying it would have been better or worse, simply different,” explained Dragiceivich.

For Dragicevich, the theater must be a dynamic experience, one very different from the television or film mediums. “It must create something truly special, a theatrical mystery, something imaginative or metaphorical, in which we observe robust physicality and live music, a non-linear narrative where the story “jumps” across time and space. I’m satisfied with the manner in which our company presents the story and I hope that the Serbian audience will be satisfied as well."

And it was. [Refugee received a standing ovation at its premiere.]

Translation by Bojana Sain-Miletic

On the fourth day of the festival, in repertory at Joakim Interfest, was the American production (written and directed by Milan Dragicevich), Refugee, presented by the Sudbina Theater Company, based in Massachusetts. Nine years ago, the Festival’s audience in Kragujevac watched Dragicevich’s earlier play, Milosevic at The Hague.

“We had a wonderful experience at this festival [nine years ago] and we had always planned to return. The opportunity finally presented itself with our new play, Refugee,” noted Dragicevich.

The play Refugee deals with a theme that unfortunately is always painfully actual and relevant, particularly today, with this specific story focusing on the Dragicevich family.

“During World War II, my mother, as an 11-year-old girl, left her village home with her father and two sisters, thinking that it would be a short temporary displacement of 2-3 months. That was in 1944, after the capitulation of Italy, followed by the German invasion of Yugoslavia. Twenty five years would pass before she returned to visit her homeland. It was an odyssey. Living in refugee camps, in Egypt on the Sinai and later in Italy, she and her family spent 7 years as displaced persons, until they received permission to relocate to America.”

Dragicevich continued: “Serbia is a country that knows the meaning of exodus and migration. My goal was to tie this story with the destiny of all peoples who are forced to leave their homes, and not only focus on my particular family history. The Serbian people, for centuries, have this “experience” – both interior displacement and exterior migration. So this play, in its own way, “widens” this story, because each of us can find oneself in its narrative. It is interesting to observe what happens to an individual when one suddenly finds oneself in a completely different or foreign environment, in another land, and one must create a new identity. And that is the question with which I grapple in this new play: How—and in what ways—do we change when we leave our homeland? I was raised in Los Angeles, near Hollywood, far from Serbia or Yugoslavia, and I always wondered how I might have developed differently had I grown up here, in the Balkans. I’m certain that my American environment shaped and influenced me in ways quite different than if I had lived here [Serbia]. I’m not saying it would have been better or worse, simply different,” explained Dragiceivich.

For Dragicevich, the theater must be a dynamic experience, one very different from the television or film mediums. “It must create something truly special, a theatrical mystery, something imaginative or metaphorical, in which we observe robust physicality and live music, a non-linear narrative where the story “jumps” across time and space. I’m satisfied with the manner in which our company presents the story and I hope that the Serbian audience will be satisfied as well."

And it was. [Refugee received a standing ovation at its premiere.]

Translation by Bojana Sain-Miletic

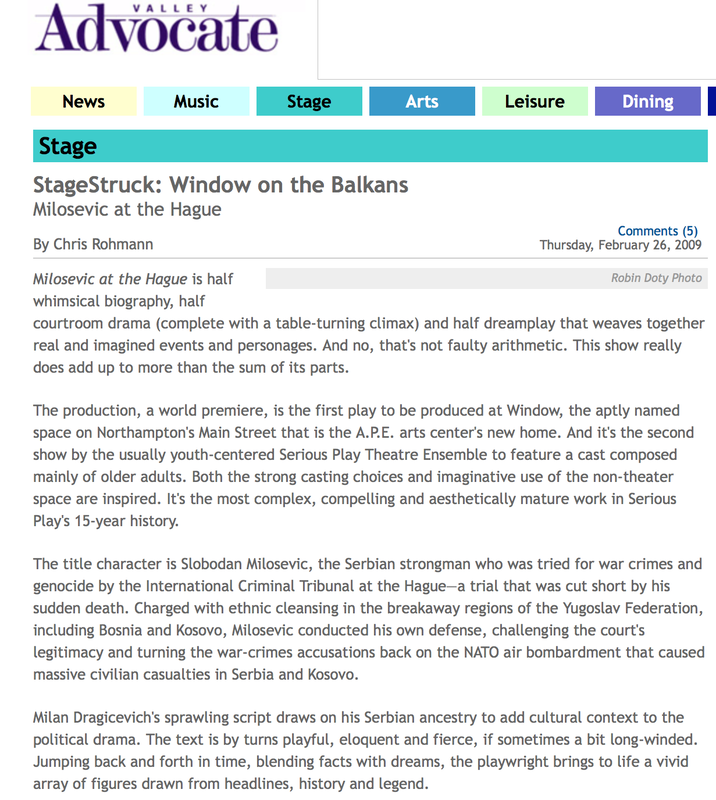

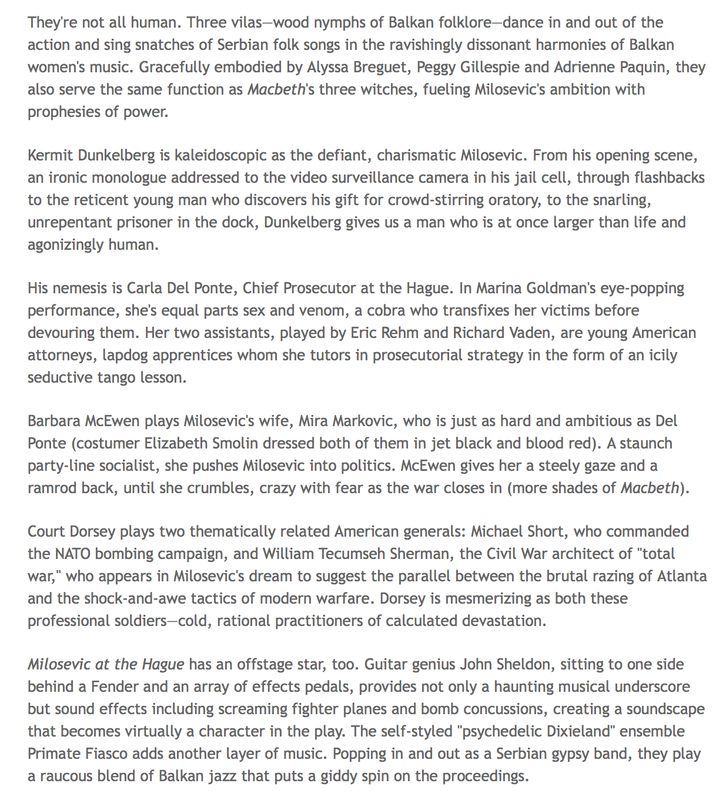

Theater review of Milan Dragicevich's MILOSEVIC AT THE HAGUE, Valley Advocate

National publication covering Milan Dragicevich's "MILOSEVIC AT THE HAGUE" at international theater festival in Serbia, Feb. 2010

TRANSLATION, from the Serbian language, of DANAS Theater Review:

October 16, 2009 (Culture Section)

FROM KOSOVO THE SHOUT OF THE VILAS

By Dragana Boskovic / Theater Review

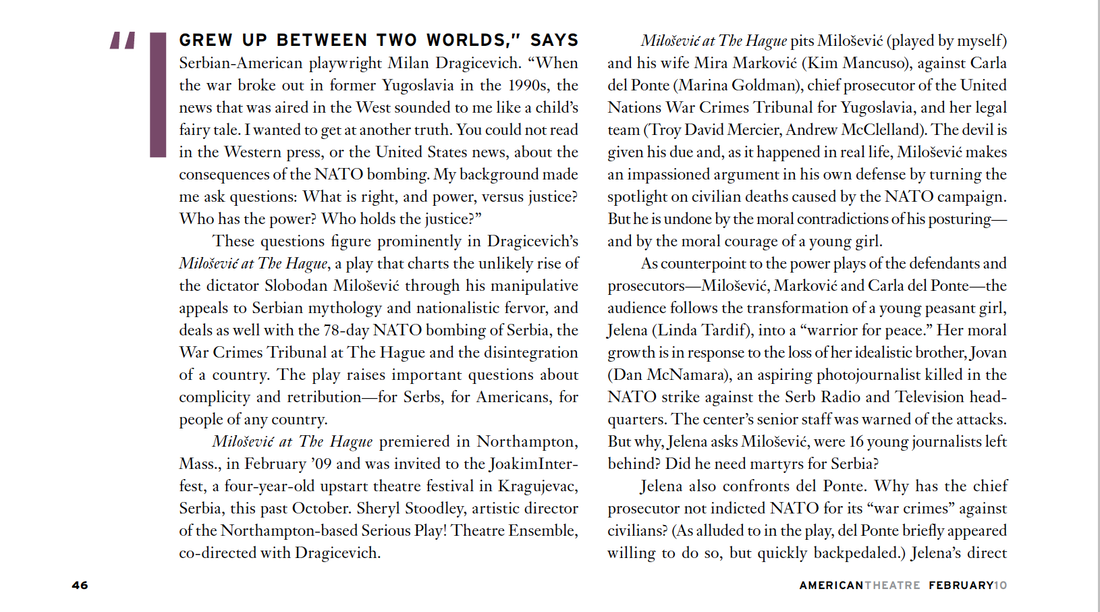

The play which describes the last days of Slobodan Milosevic in the Hague and

which ends with his death is a very effective and honest work. It is an honest

attempt, through an authentic theatrical language, to show a very complex

psychological-sociopathological-political story about the roots of Milosevic’s

mindset, as well as the hypocrisy of the West’s bombing of Serbia. Particularly

intriguing is the fact that this play arrives from America, not from Serbia, which

has, to date, not dealt with this thorny subject in any serious manner.

Those who expected political pamphleteering, with clear judgments for a winner,

did not receive such an outcome. Milan Dragicevich wrote a text that attempts to

place into collision two parties who do not hear one another. Even though there

are visual screens or panels placed above the audience, there are no actual

photographs of war crimes displayed on them, though they are verbally

described in vivid detail. Neither are there images of the bombing of the

Belgrade Television and Radio Center, though the evidence for this horrific event

has been truthfully described. Milan Dragicevich and the Serious Play Theatre

Ensemble, led by Artistic Director Sheryl Stoodley, co-director of the play, have

depicted with integrity a series of events that are especially close to us so that we

might better be able to interpret them through the symbols of theater.

To better underscore the symptoms of war crimes, on one side and the other, the

author introduces a choir of three “vilas,” who, as in Macbeth, warn Milosevic,

ask him for answers, and weep for the Serbian people. Peggy Gillespie,

Adrienne Paquin, and Alyssa Breguett, who play the vilas, wonderfully sing the

ancient Kosovo melodies in perfect Serbian. Also, there are three brass

musicians, as well as one electric guitarist, in the production. The splendid

singing of our old songs can be credited to Milan Dragicevich who, even though

born in the United States, closely embraces our traditions through his

engagement with them. The play was translated into Serbian by Bojana

Sain-Miletic.

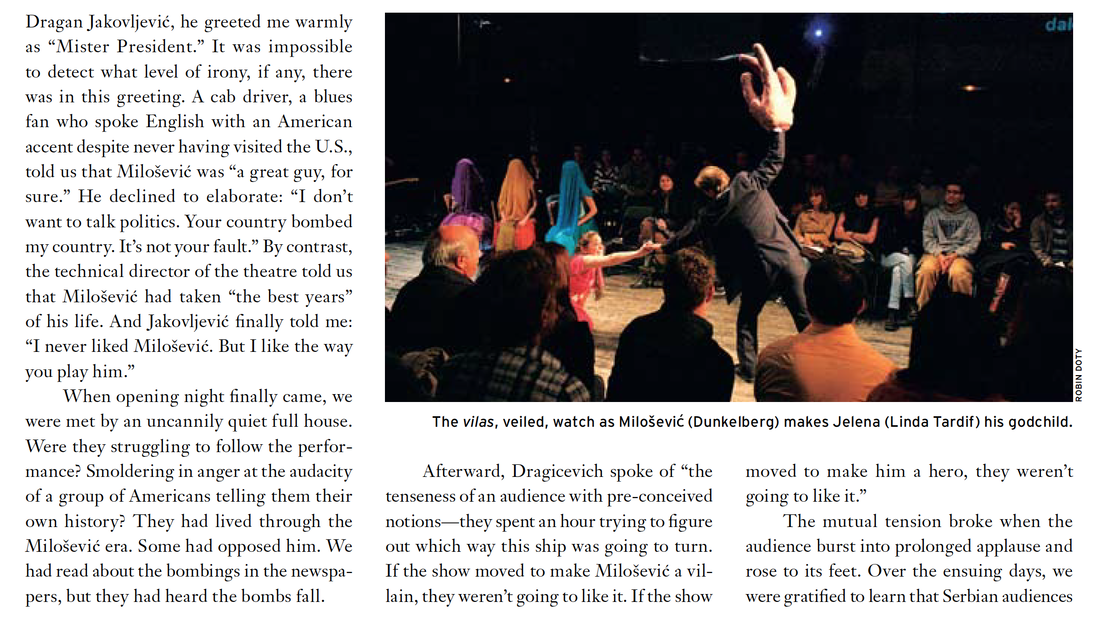

On “our” side are Jelena (precisely and touchingly played byLinda Tardiff)

and Jovan (Dan McNamara), twins from Velika Hoca, as well as their

Uncle Rade (the Dickensian Nick Simms). The two kids, as Milosevic’s

godchildren, are his conscience, and Jelena will, upon visiting him at the Hague,

finally and correctly accuse him of the misfortune that has befallen us.

Arrayed on the American side of the indictment are the all-encompassing Carla

del Ponte (the excellent Marina Goldman) with her two “appendages”-lawyers,

played by Troy Mercier and Andrew McClelland. Through this “troika” the

authors have succeeded in showing that the trial at the Hague is a kind of erotic

game, in which Madam Del Ponte “plays” with others primarily for her own self

gratification.

An intriguing device by playwright Dragicevich (actor, writer, university

theater professor) involves Milosevic’s system of intimate defense

(though in this production he does not doubt himself or his spouse, played by

Kim Mancuso), specifically his introduction of an dream-like character—General

Tecumseh Sherman (the effective Court Dorsey), who fought against the South

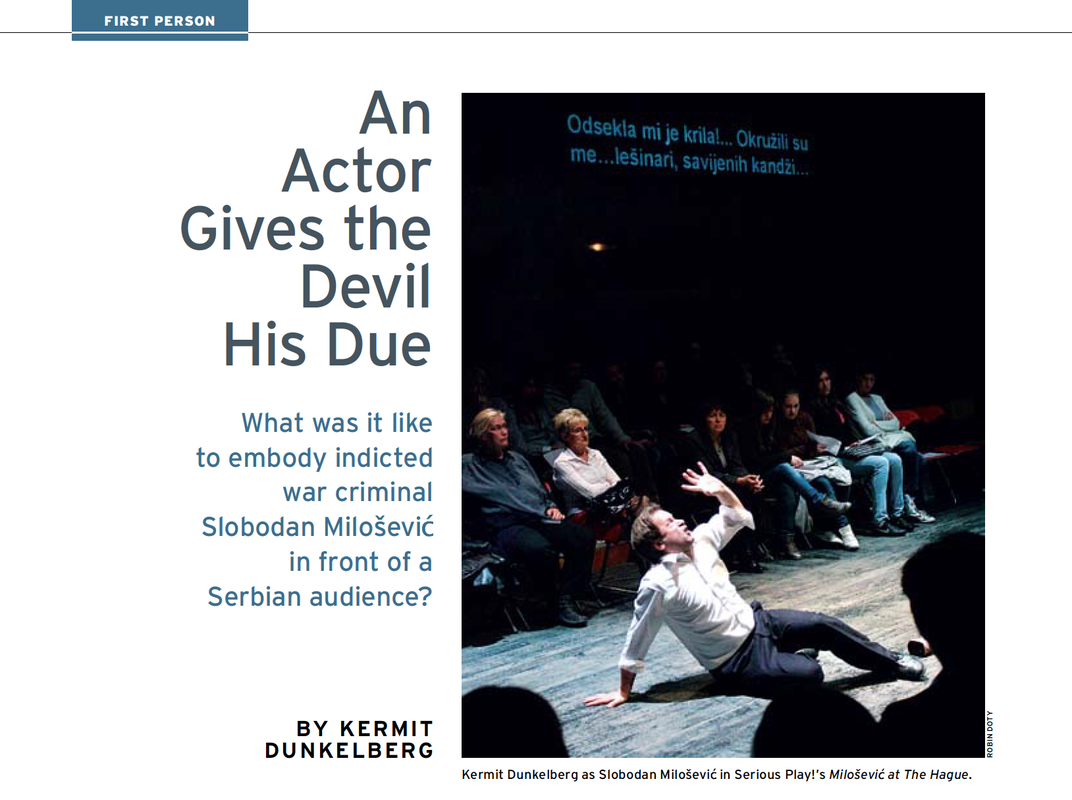

and confides that he did so out of love, as an avenging angel. Finally, Kermit

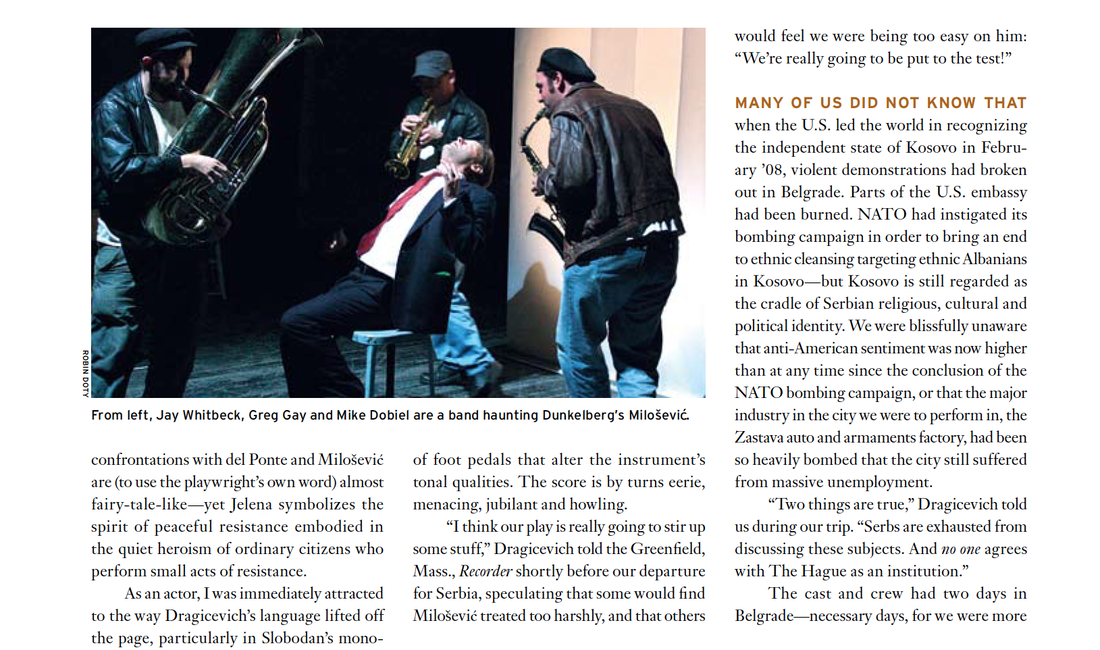

Dunkelberg, as Slobodan Milosevic, who first confesses to his security camera,

which monitors him at the Hague cell, and then sings the patriotic “Igrale se

Delije” (!) and dances and plays—he has the foundational strength of a man who

is led by his diseased ambition. Nonetheless, the authors were able to grasp the

real reasons, as well as the psychological motives for Milosevic’s faulty decisions

and for his transformation.

Since it is a theatrical event, this story is difficult to understand objectively. The story,

through physical theater, authentic sound, real dramatic moments (such as Jelena’s

arrival at the Hague), excellent use of the grotesque (such as the dancing of Carla del Ponte),

skirting petty realism (like the statistical tally of crimes on both sides) succeeded in

moving the play away from political grandstands and into the sphere of human empathy

for any theatre audience. Would the contemporaries of Richard III or Macbeth think that Shakespeare’s character really resembles him? And that it is truthful?

This production of “Milosevic at the Hague” is honest, not at all showy, a high

quality attempt to tell this story, which is, as in ancient times, placed in the

sphere of the moral and personal and universal, under conditions which still

prevail, where people on both sides are not satisfied with their political leaders

(and the dead cannot speak). This story features soaring theatrical language, an

excellent script by Milan Dragicevich, and effective movements directed by

Sheryl Stoodley. Joakiminterfest in Kragujevac, and its selector and director,

Dragan Jakovljevic, have succeeded in allowing this production to “shout out”

from Kragujevac, and that “shout” will resonate, with others, for a long time.

Translation by Bojana Sain-Miletic

October 16, 2009 (Culture Section)

FROM KOSOVO THE SHOUT OF THE VILAS

By Dragana Boskovic / Theater Review

The play which describes the last days of Slobodan Milosevic in the Hague and

which ends with his death is a very effective and honest work. It is an honest

attempt, through an authentic theatrical language, to show a very complex

psychological-sociopathological-political story about the roots of Milosevic’s

mindset, as well as the hypocrisy of the West’s bombing of Serbia. Particularly

intriguing is the fact that this play arrives from America, not from Serbia, which

has, to date, not dealt with this thorny subject in any serious manner.

Those who expected political pamphleteering, with clear judgments for a winner,

did not receive such an outcome. Milan Dragicevich wrote a text that attempts to

place into collision two parties who do not hear one another. Even though there

are visual screens or panels placed above the audience, there are no actual

photographs of war crimes displayed on them, though they are verbally

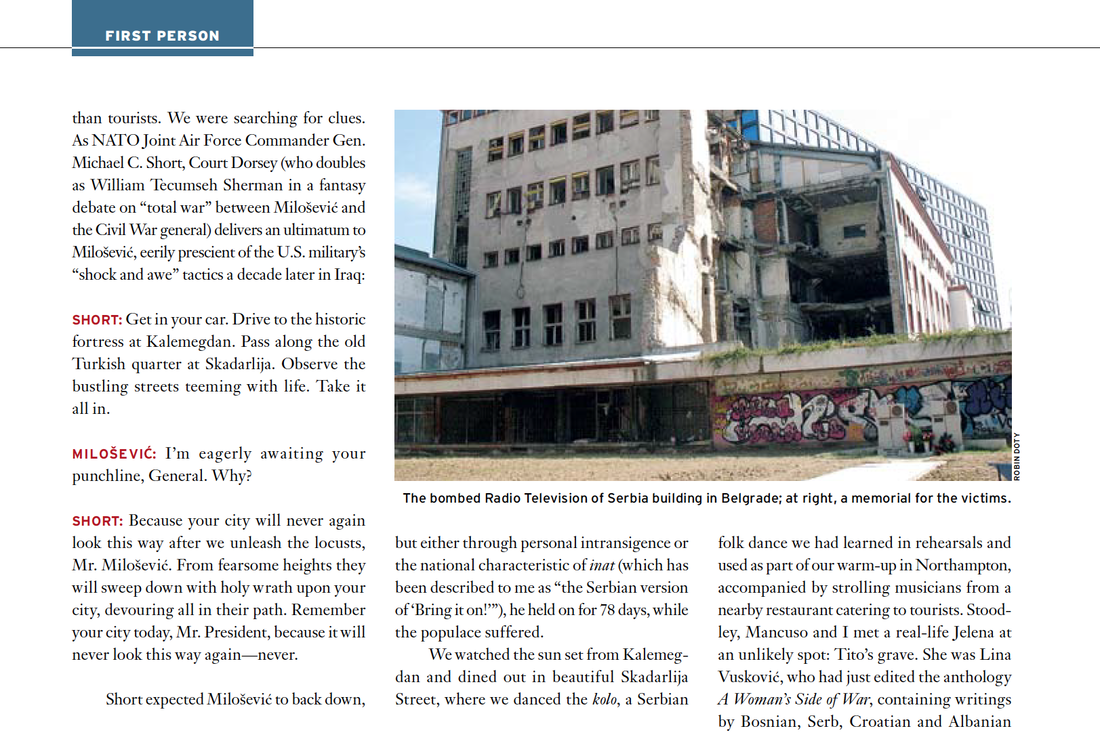

described in vivid detail. Neither are there images of the bombing of the

Belgrade Television and Radio Center, though the evidence for this horrific event

has been truthfully described. Milan Dragicevich and the Serious Play Theatre

Ensemble, led by Artistic Director Sheryl Stoodley, co-director of the play, have

depicted with integrity a series of events that are especially close to us so that we

might better be able to interpret them through the symbols of theater.

To better underscore the symptoms of war crimes, on one side and the other, the

author introduces a choir of three “vilas,” who, as in Macbeth, warn Milosevic,

ask him for answers, and weep for the Serbian people. Peggy Gillespie,

Adrienne Paquin, and Alyssa Breguett, who play the vilas, wonderfully sing the

ancient Kosovo melodies in perfect Serbian. Also, there are three brass

musicians, as well as one electric guitarist, in the production. The splendid

singing of our old songs can be credited to Milan Dragicevich who, even though

born in the United States, closely embraces our traditions through his

engagement with them. The play was translated into Serbian by Bojana

Sain-Miletic.

On “our” side are Jelena (precisely and touchingly played byLinda Tardiff)

and Jovan (Dan McNamara), twins from Velika Hoca, as well as their

Uncle Rade (the Dickensian Nick Simms). The two kids, as Milosevic’s

godchildren, are his conscience, and Jelena will, upon visiting him at the Hague,

finally and correctly accuse him of the misfortune that has befallen us.

Arrayed on the American side of the indictment are the all-encompassing Carla

del Ponte (the excellent Marina Goldman) with her two “appendages”-lawyers,

played by Troy Mercier and Andrew McClelland. Through this “troika” the

authors have succeeded in showing that the trial at the Hague is a kind of erotic

game, in which Madam Del Ponte “plays” with others primarily for her own self

gratification.

An intriguing device by playwright Dragicevich (actor, writer, university

theater professor) involves Milosevic’s system of intimate defense

(though in this production he does not doubt himself or his spouse, played by

Kim Mancuso), specifically his introduction of an dream-like character—General

Tecumseh Sherman (the effective Court Dorsey), who fought against the South

and confides that he did so out of love, as an avenging angel. Finally, Kermit

Dunkelberg, as Slobodan Milosevic, who first confesses to his security camera,

which monitors him at the Hague cell, and then sings the patriotic “Igrale se

Delije” (!) and dances and plays—he has the foundational strength of a man who

is led by his diseased ambition. Nonetheless, the authors were able to grasp the

real reasons, as well as the psychological motives for Milosevic’s faulty decisions

and for his transformation.

Since it is a theatrical event, this story is difficult to understand objectively. The story,

through physical theater, authentic sound, real dramatic moments (such as Jelena’s

arrival at the Hague), excellent use of the grotesque (such as the dancing of Carla del Ponte),

skirting petty realism (like the statistical tally of crimes on both sides) succeeded in

moving the play away from political grandstands and into the sphere of human empathy

for any theatre audience. Would the contemporaries of Richard III or Macbeth think that Shakespeare’s character really resembles him? And that it is truthful?

This production of “Milosevic at the Hague” is honest, not at all showy, a high

quality attempt to tell this story, which is, as in ancient times, placed in the

sphere of the moral and personal and universal, under conditions which still

prevail, where people on both sides are not satisfied with their political leaders

(and the dead cannot speak). This story features soaring theatrical language, an

excellent script by Milan Dragicevich, and effective movements directed by

Sheryl Stoodley. Joakiminterfest in Kragujevac, and its selector and director,

Dragan Jakovljevic, have succeeded in allowing this production to “shout out”

from Kragujevac, and that “shout” will resonate, with others, for a long time.

Translation by Bojana Sain-Miletic

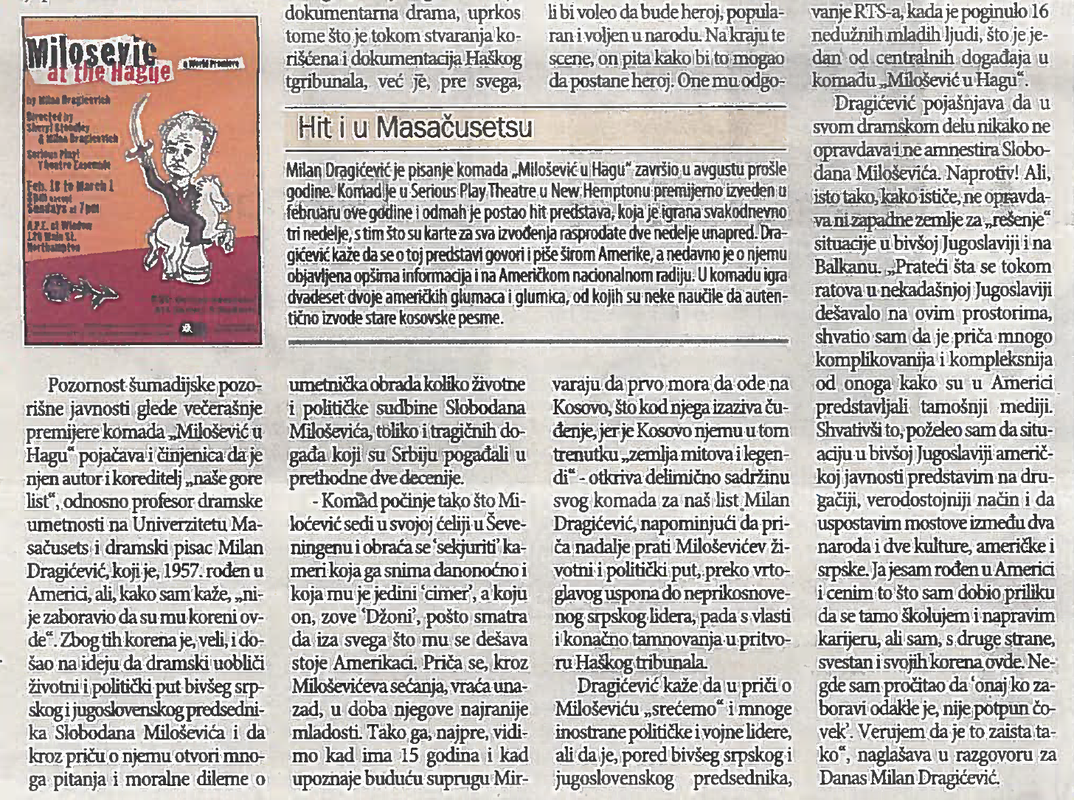

The following newspaper article, from DANAS, a national newspaper in Serbia, is press coverage announcing the premiere of "Milosevic at The Hague" at Joakim Interfest in Kragujevac, Serbia.